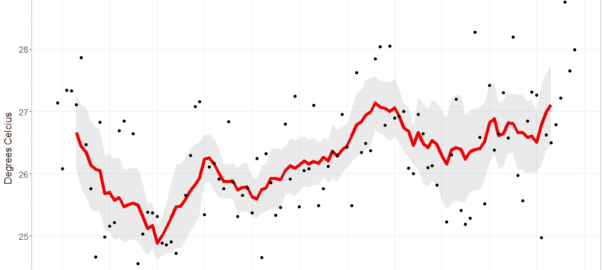

Recently, I decided to crunch some data from the Australian Bureau of Meteorology (which I’ll just call BoM) to assess some of my own perceptions about how the climate in my home city of Brisbane had changed throughout my lifetime. As always, I performed the analysis in Knime, a free and open software platform that allows you to do highly sophisticated and repeatable data analyses without having to learn how to code. Along the way, I also took the opportunity to sharpen my skills at using R as a platform for making data visualisations, which is something that Knime doesn’t do quite as well.

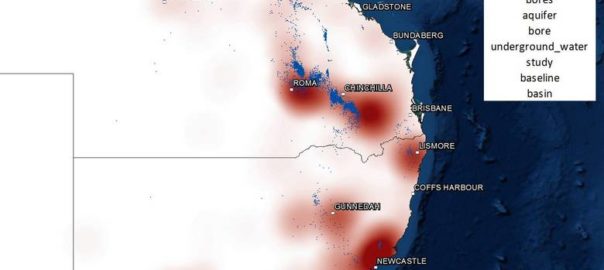

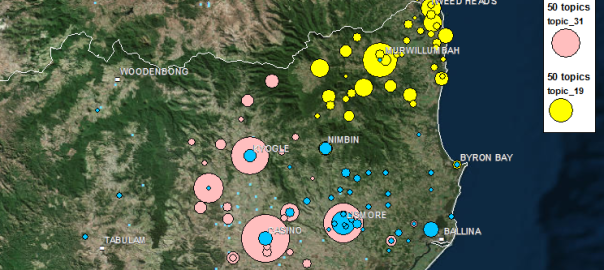

The result of this process is HeatTraKR, a Knime workflow for analysing and visualising climate data from the Australian Bureau of Meteorology, principally the Australian Climate Observations Reference Network – Surface Air Temperature (ACORN-SAT) dataset, which has been developed specifically to monitor climate variability and change in Australia. The workflow uses Knime’s native functionality to download, prepare and manipulate the data, but calls upon R to create the visual outputs. (The workflow does allow you to create the plots with Knime’s native nodes, but they are not as nice as the R versions.)

I’ve already used the HeatTraKR to produce this post about how the climate in Brisbane and Melbourne (my new home city) is changing. But the workflow has some capabilities that are not showcased in that post, and I will take the opportunity to demonstrate these a little later in the present post.

Below I explain how to install and use the HeatTraKR, and take a closer look at some of its outputs that I have not already discussed in my other post. Continue reading HeatTraKR – A Knime workflow for exploring Australian climate data