GameStop the press!

Remember GameStop? You know, the video game retailer whose decaying share price exploded after a bunch of Reddit users bought its stock and succeeded in bankrupting a hedge fund who was trying to short it? Yeah, that was nearly a week ago now, so my memory of it is getting hazy. I mostly remember all the explainers about how the share market works and what a short squeeze is. And the thought pieces about how this kind of coordinated market behaviour is nothing criminal, just ordinary folk playing the big boys at their own game and finally winning. And the memes: who can forget the memes? Well, me, for a start.

Somewhere amid the madness, I decided that I should harvest some Twitter data about this so-called GameStop saga (can something really only be a saga after only three days?) to capture the moment, and to see whose hot takes and snide remarks were winning the day in this thriving online marketplace of shotposts and brainfarts.

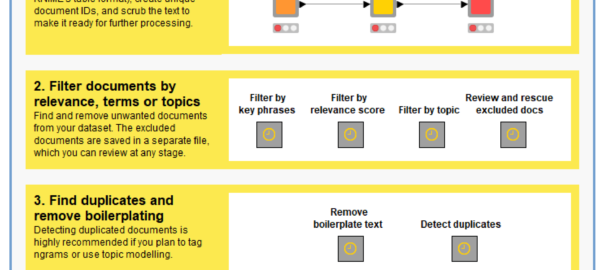

I confess that I had another motive for doing this as well, which was to provide some fodder for my TweetKollidR workflow, which turns Twitter datasets into pretty and informative pictures. The TweetKollidR is a workflow for the KNIME Analtyics Platform that I developed while locked down for three months in the latter half of 2020. I’ve made the workflow publicly available on the KNIME Hub, but it is still in need of road-testing, having been used (by me, at least) to analyse only two issues — the Covid-19 lockdown that spurred its genesis, and the wearisome public discourse about Australia Day. I felt that it was time to test the workflow on an issue that was not so close to home.

So, using the TweetKollidR workflow to connect to Twitter’s Search API, 1 I collected just over 50,000 tweets containing the terms gamestop or game stop. Because I am not paying for premium access to the API, I was only able to grab tweets that were made within about 24 hours of the search (usually you can go back in time up to a week, but the sheer volume of activity around this topic might have shortened the window offered by the API). The 50,000 tweets in the dataset therefore cover just two days, namely 28 and 29 January 2021.

Let’s take a squiz! (By which, for the non-Australians among you, I mean a look or glance, esp an inquisitive one.) Continue reading GameStop on Twitter: a quick squiz at the short squeeze

Notes:

- API stands for application programming interface, which is essentially a protocol by which content can be requested and supplied in a machine-readable format, rather than as eye candy. ↩